CHAPTER 3

From Alcohol Can Be a Gas! Fueling an Ethanol Revolution for the 21st Century, © author David Blume.

THE PERMACULTURE SOLUTION TO FOSSIL FUEL DEPENDENCY

TODAY’S CORN FARMERS WILL BEGIN TO ASK THEMSELVES, “WHY NOT GROW 800- TO 1000-GALLON-PER-ACRE CROPS AND STILL BE ABLE TO GROW A COVER CROP OVER THE WINTER, TO BE TURNED IN, PROVIDING FERTILIZER AND ORGANIC MATTER TO GROW THE NEXT CROP?” WHY NOT, WHEN IT NOT ONLY IS PRODUCTIVE AND PROFITABLE, BUT GIVES US A CLEANER ENVIRONMENT AND HEALTHY SOIL? WHEN FARMERS REALIZE THEIR CO-OP CAN GROSS $2300 PER ACRE JUST ON THE ALCOHOL, AND CAN ALSO DEMOLISH ALMOST ALL CHEMICAL INPUT COSTS—IT BECOMES DIFFICULT TO CONSIDER A REASON NOT TO DO IT.

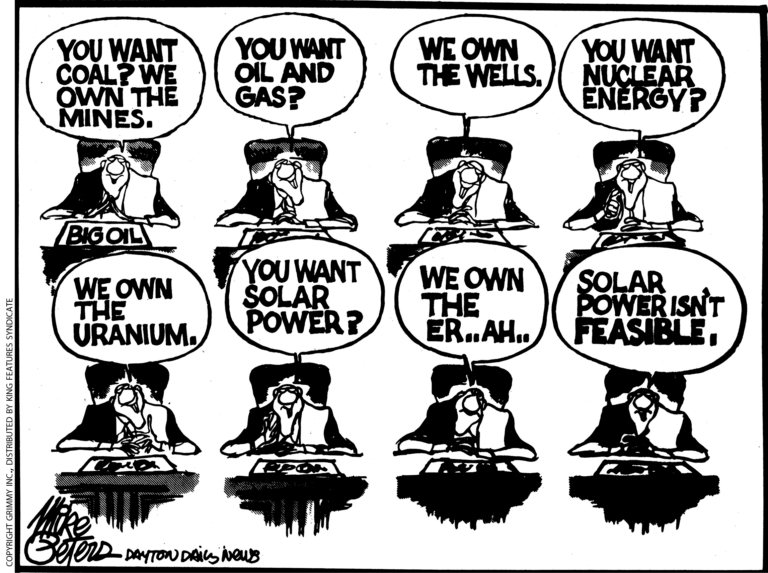

As we showed in the last chapter, industrial agriculture and its components—oil-based fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides—are harmful to the planet. A nationwide switch to organic farming is in order. But it can’t work if we maintain a monoculture-based system, with its present emphasis on corn farming. Much of America’s farmland is below 2% organic matter. At 2%, the soil biology collapses—and, with it, the fertility needed to grow crops. More and more chemical fertilizer is needed to prop up production on sterilized soil.

The “Green Revolution” and Permaculture

A lot of people think that the “Green Revolution”—marked by the advent of monocultures, pesticides, herbicides, and chemical fertilizers some 60 years ago—produces more food per acre than older methods of agriculture. It emphatically does not. In fact, a Mexican campesino using simple hand tools to grow a polyculture of corn, beans, and squash can produce, on a dry-weight basis, far more food per acre than the farmer of the most modern U.S. Midwestern cornfield—food worth far more money on a net basis.1 Unlike subsidized Green Revolution farmers, the campesino would not survive if his farming were only 30% efficient in using its major energy input (sunlight) or if it were dependent on expensive consumable products (herbicides, pesticides, fertilizers) that damaged the operating equipment (soil).

More than a half-century of this so-called Green Revolution has created our current urgent need for permaculture ethanol systems to solve the many agricultural and energy woes left in its wake. My hope is that an appeal to farmers’ bottom lines, as well as a national consensus for a cleaner environment, will motivate change toward permaculture.

As you will see later in this book, there are many crops that can produce much larger amounts of alcohol fuel than a monocultural crop such as corn. A key to the success of the permaculture system is crop rotation, where different nutrients are used each season and nothing becomes depleted. Right now, the only common rotation in the Midwest consists of corn and soybeans. If you had four to eight different energy crops rotating, the demands on the soil would be very much reduced and could even be complementary.

“Then why should the farmer pay an ever-increasing price for gasoline when he can produce all the alcohol he needs and a lot more on his own farm?”

—HENRY FORD, DETROIT NEWS, DECEMBER 13, 1916

As long as much of the organic matter from production is returned to the soil—as in permaculture—an agricultural system will increase in fertility each year. The present agricultural system destroys topsoil and, therefore, fertility. Once the level of organic matter in the soil reaches around 5%, organic farmers need only about five tons of compost per acre per year to maintain fertility. Spread evenly over an acre, this would appear as a light dusting. With more organic matter than that, farmers would build topsoil depth and soil biological activity.

For example, if you were to grow relatively shallow-rooted corn one year, the next year you might grow fodder beets that will go several feet deep, using their huge system of roots to bring potassium and phosphorus up near to the surface. When you harvest the massive, 15-pound beet, it is only the top of an inverted conical pyramid of roots that fan out to probably more than three feet in diameter at the soil surface, tapering to a point five feet down. The part we harvest is less than half the weight of this entire root system. Fungi and earthworms can feed on the many pounds of smaller roots left behind throughout the soil, freeing the phosphorus and potassium for the next crop.

With rotation of crops grown for energy, today’s corn farmers will begin to ask themselves, “Why not grow 800- to 1000-gallon-per-acre crops like fodder beets, Jerusalem artichokes, or sweet sorghum—and still be able to grow a cover crop like fava beans over the winter, to be turned in, providing fertilizer and organic matter to grow the next crop?” Why not, when it not only is productive and profitable, but gives us a cleaner environment and healthy soil? When farmers realize their co-op can gross $2300 per acre just on the alcohol, and can also demolish almost all chemical input costs by returning (for example) the spent beet pulp, or the manure from animals eating the beet pulp, into the soil—it becomes difficult to consider a reason not to do it.

Polyculture, Photosynthesis, and Photosaturation

Polyculture is an advanced method of agriculture that obtains the multiple benefits of crop rotation by growing many crops simultaneously. Polyculture dramatically increases the productivity of photosynthesis by eliminating photosaturation, or solar saturation, the point at which a plant’s photosynthetic machinery is shut down by excess sunlight.

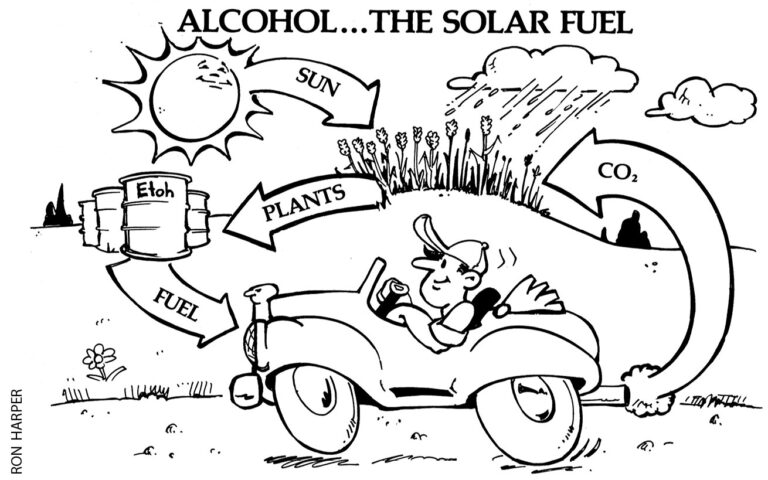

Simply put, photosynthesis is carbon dioxide (CO2) plus water (H2O) plus sunlight (energy for the reaction), which creates six molecules of CH2O (glucose) plus a molecule of oxygen (O2). Glucose is the basis of starch and cellulose.

A wide cross-section of the plant world photosaturates at 30% of a day’s total sunlight, at which point more sunlight will not increase photosynthesis. This means that most plants grown in full sunlight stop growing in the middle of the day due to photosaturation, and don’t resume growing again until the afternoon. And even if they can take the solar stress, they “waste” two-thirds of the surplus sunlight falling on them. Why? Because if a plant species needs unobstructed full sunlight all day, and then some tree extends a branch and shades it, the species will go extinct.

Fig. 3-2 Photosaturation. Winter squash visibly demonstrate their saturation by excess sunlight. This well-irrigated plant is “wilting” at two p.m. in mid-September at a cool 60˚F; in this way the plant deflects most of the direct sunlight. Note how much self-formed shade the leaf has created.

But plants that have evolved to use a fraction of the available sunlight have also evolved to cooperate in a natural polyculture of mixed plants. A good example is winter squash. On seed packets, gardeners are told to plant it “in full sun.” Pumpkins, butternut, and Delicata squashes wilt in the middle of the day when exposed to full sun because their huge leaves have evolved to use the dim light in their original home, climbing through the trees in a tropical rainforest. They wilt in order to deflect the excess sunlight. Many people incorrectly assume that the plants are dehydrated and water them excessively. In the later afternoon, the leaves stiffen up again and look healthy. The gardeners pat themselves on the back for a job well done and then are incredulous the next day when the leaves wilt again.

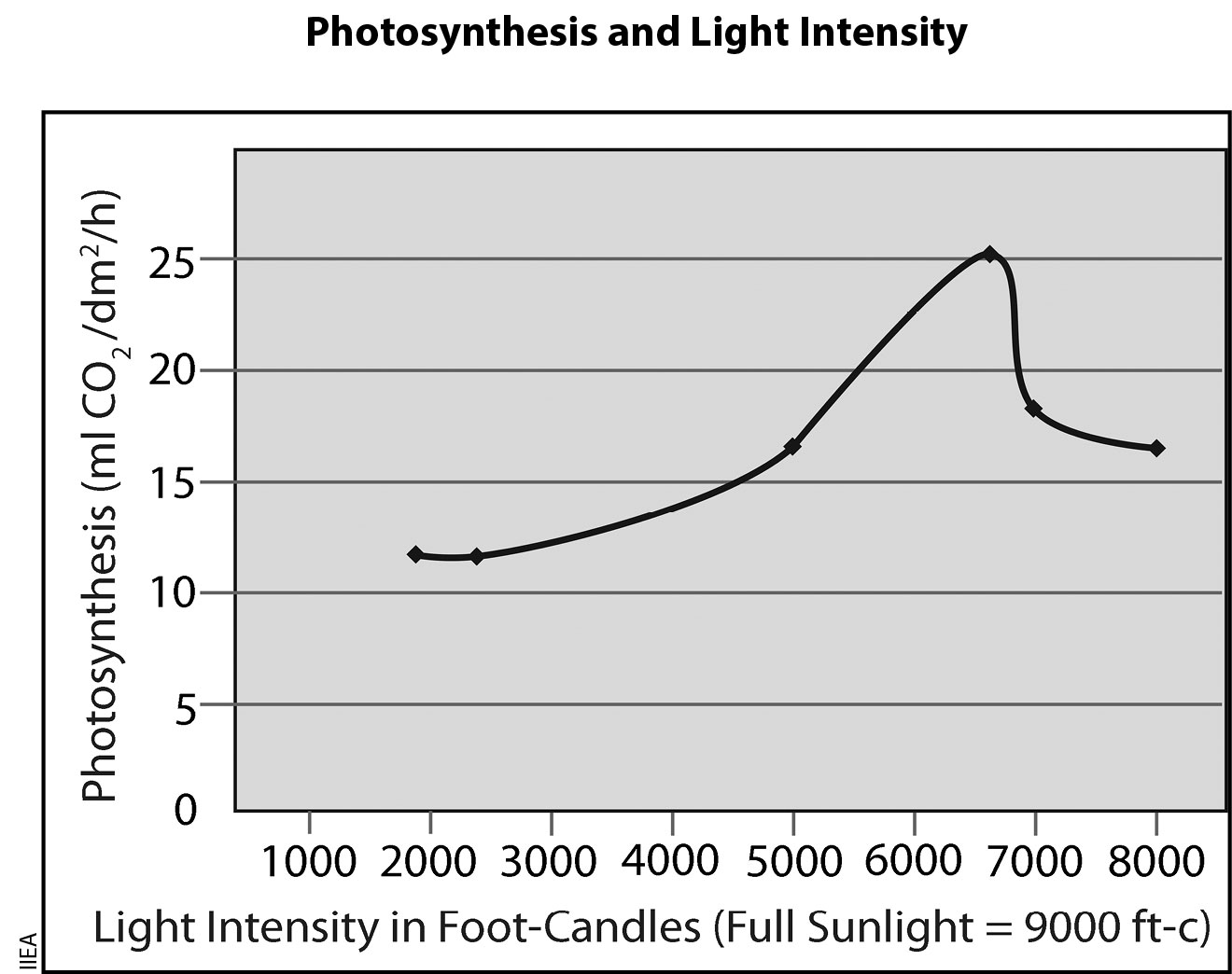

Fig. 3-3 Solar saturation in sugarcane. It’s clear that as sunlight reaches its highest intensity in the middle of the day (9000 foot-candles (ft-c)), photosynthesis drops off dramatically and comes to a complete stop. Providing a light shade over the crop keeps carbohydrate production high throughout the day.

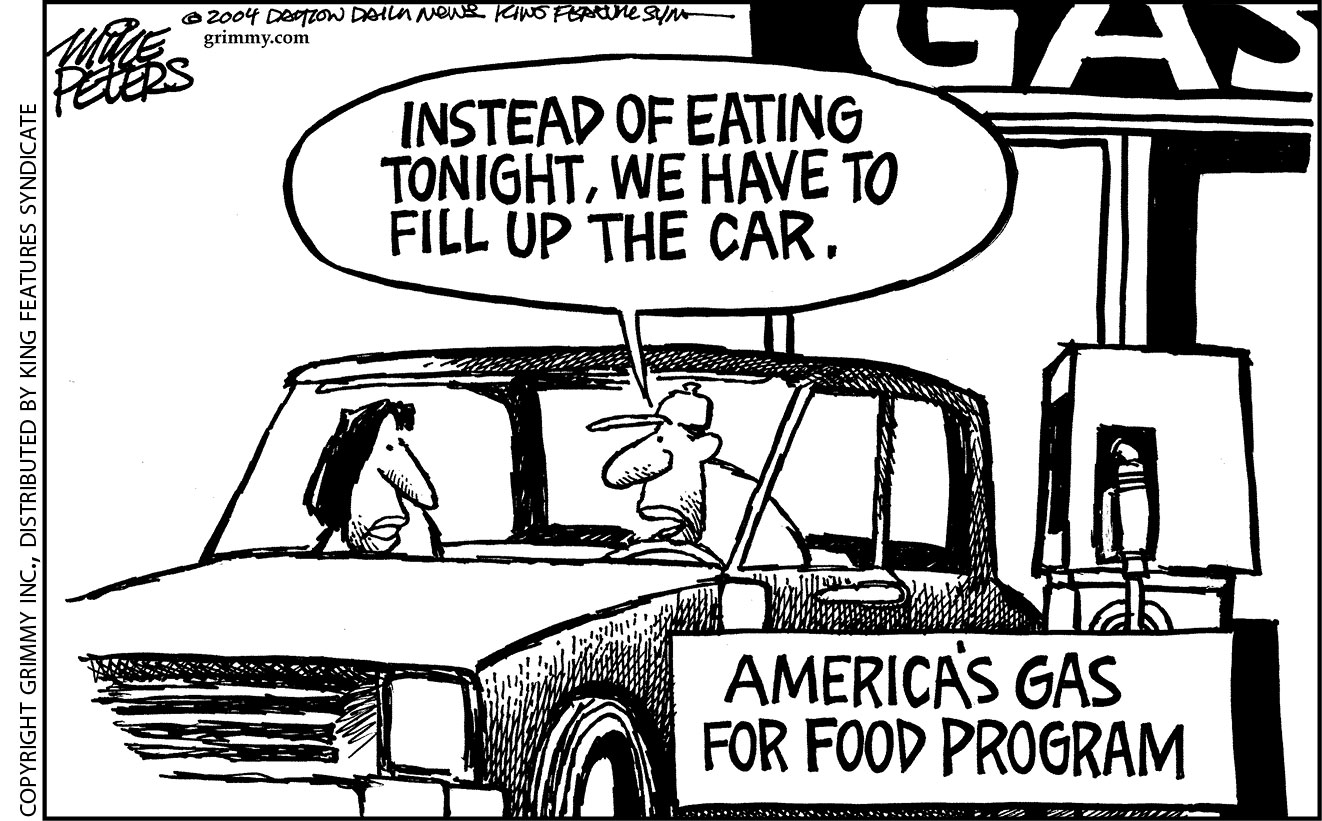

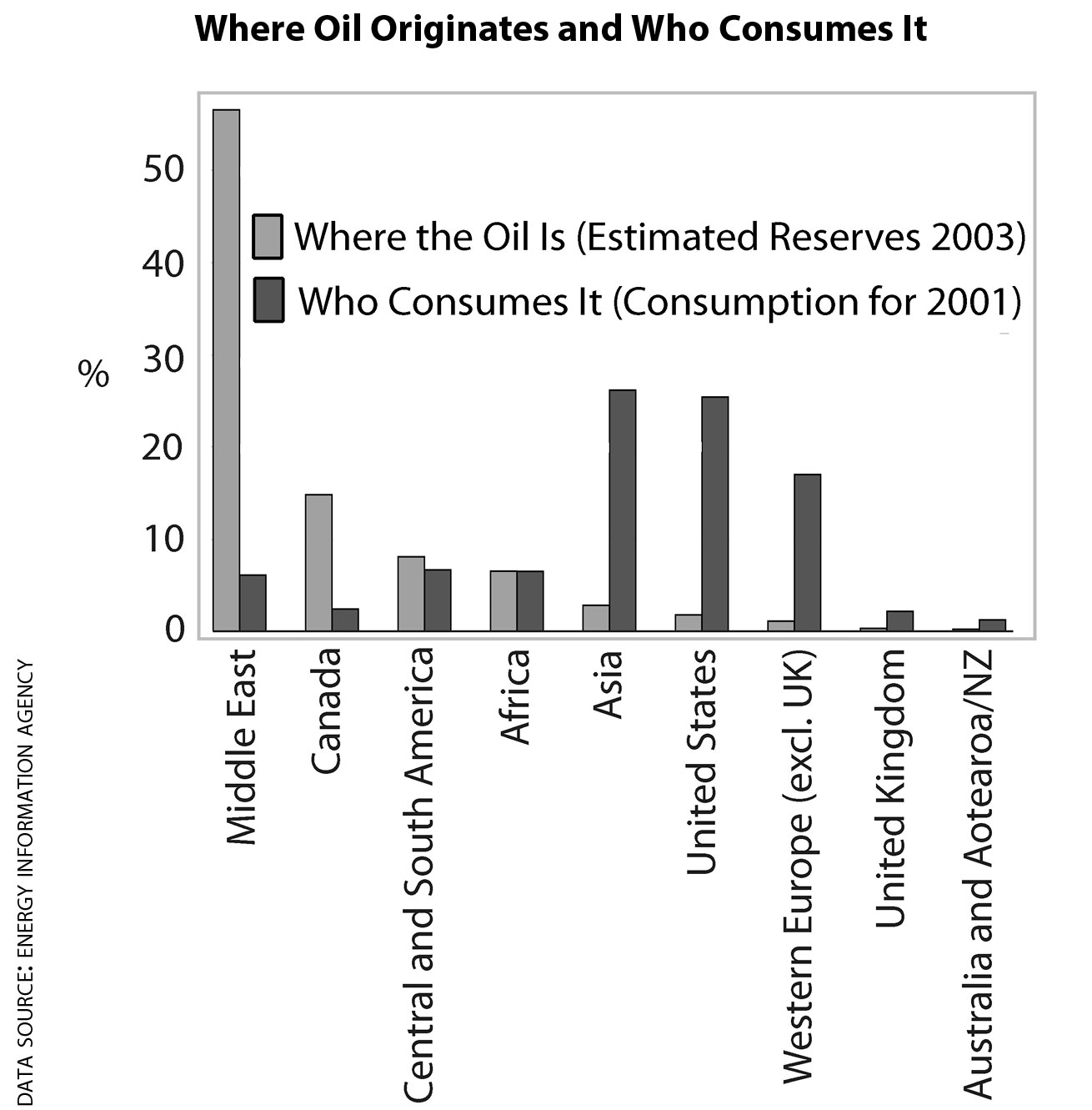

Fig. 3-4 Where the oil is and who consumes it.6 The fact that the countries that use the oil are far from its source is both energy-inefficient and the source of potential conflict over possession of resources. If all countries produced some or all of their energy from the sunlight falling on them, we’d have a lot fewer problems.7

The first way to prevent photosaturation is to plant multiple canopies in a polyculture to cross-shade. For example, in a polyculture of corn, beans, and squash, the corn and beans shade each other, with the beans climbing up the corn, and both shade the squash growing underneath. In this way, each crop is harvesting about 30% of the sunlight, and little goes to waste. (Why doesn’t corporate agribusiness do this? Because it’s not a machine-friendly system and would result in higher dependence on labor, the increase in net profit notwithstanding.)

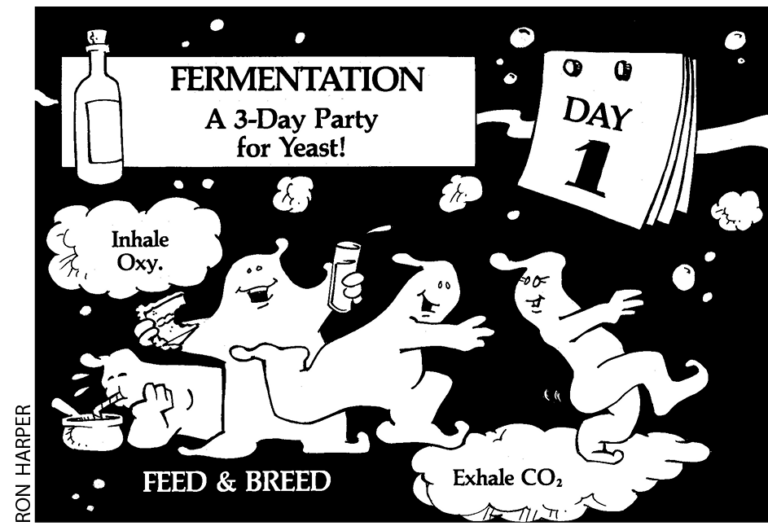

Another way to extend photosaturation limits (and also to initiate or extend photosynthesis in low-light conditions) is to add carbon dioxide, which alcohol fuel-makers can supply from their fermentation tanks. As you will see later, when yeast ferment carbohydrates to alcohol, they convert about half of what they eat into carbon dioxide, which they “exhale.”

A small additional amount of carbon dioxide can mean plants will continue to photosynthesize down to 0.5% of average sunlight instead of being inactive below 5%.9 with none of this expected to go to the U.S. at present, because of our trade barriers. Photosynthesis would therefore start earlier and end later in the day; or a denser overstory of crops and shade would be permissible.

With higher amounts of carbon dioxide, photosaturation levels are increased, allowing unshaded plants to waste less sunlight in the middle of the day—resulting in up to triple the biomass produced during what normally would be a period of stress and no growth. Long-term study shows tripled yields of biomass and fruit in tree crops with carbon dioxide enrichment, even outside of greenhouses.10

A Great System for Feeding Plants

We were all taught in biology class that plants need various nutrients, such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. We were taught that plants absorb the water-soluble nutrients via the roots, and that all nutrients travel upward to make the building blocks of plant matter. The setup was portrayed as a one-way street, with the plants extracting what they need from the soil, and with each plant in competition with every other plant for scarce resources.

But, in reality, plants give back to the soil, through the roots, as much as or more than they receive. Furthermore, each plant is not a Lone Ranger, but a part of a larger community of below-ground organisms that provide sustenance to the plant and receive food in return.

Virtually every plant depends on special types of fungi to help it acquire food. These are called mycorrhizae; myco means fungus, and rhiza means root. The primary underground relationship is based on mycorrhizal symbiosis, a process that is key to understanding how plants are nourished.

At the heart of biological farming is organic matter, which is anything that rots. Leaves, twigs, manure, your jeans, and paper are all organic matter. Organic matter is consumed by both fungi and bacteria as the first step, at the bottom band of the soil’s living biomass pyramid.

Most of us are familiar with the above-ground biomass pyramid. In rough terms, the base band of that pyramid is plants; the smaller band above that is plant-eating animals; and above that are carnivores, sometimes topped off by a top carnivore.

In the soil’s living biomass pyramid, fungi and bacteria form the base; next up is a smaller biomass band consisting primarily of tiny microscopic mites that look vaguely like ticks and that eat the fungi and bacteria, devouring maybe ten times their weight. Go up the pyramid another step, and you’ll find a smaller population of slightly larger predatory mites, which eat ten times their weight in the smaller mites. Another level up, and you get into “large” but still microscopic creatures, such as springtails and nematodes, that generally eat both fungi and predatory mites. Finally, you get up to things you can see, such as earthworms and the like.

The bacteria and fungi, while not animals, are definitely not plants. Fungi and soil animals don’t make their own food from sunlight or breathe carbon dioxide. They all eat or decompose something, they breathe oxygen, and they reproduce. And they do one other, very important, thing. They poop. Nine-tenths of all that eating ten times their own weight at each level ends up as poop. This microscopic creature poop is much of what plants need for food.

How it gets into the plants is another story. The fungi are after the same thing as any kid—mainly sugar. Unlike plants, fungi can’t make sugar, so they need to take it from plants. Now, these fungi aren’t generally parasites. They don’t just take nutrients and kill the plant, which would be the road to evolutionary extinction. They engage in trade.

Fungi dissolve rocks, organic matter, microscopic creature poop, leaves, dead bacteria, and almost anything they touch, by exuding powerful fluids such as acids or hydrogen peroxide. They then soak up the dissolved nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium) and pump them into the plant in return for the sugar. Both the plants and the fungi think they are getting a great deal. After all, plants make a huge surplus of sugar over what they need for growth, and fungi can dissolve and absorb much larger quantities of soluble minerals than they need to thrive. As with any permacultural system, surpluses need to be put to work—and so both the plants and fungi cooperatively trade their surpluses.

Plants pump 60 to 85% of the sugar produced in their leaves into their roots, and more than half of that goes to feeding mycorrhizae, or exuding the sugar solution out into the soil for bacteria and other microbes to eat.12 For instance, strawberries can grow under a dense pine forest, where no direct sunlight penetrates. The mycorrhizae transfer sugar that originates with the pines to the strawberries in exchange for something the strawberry produces that the fungi want to eat. So, that sweet wild strawberry you pick is actually flavored by pine sugar.

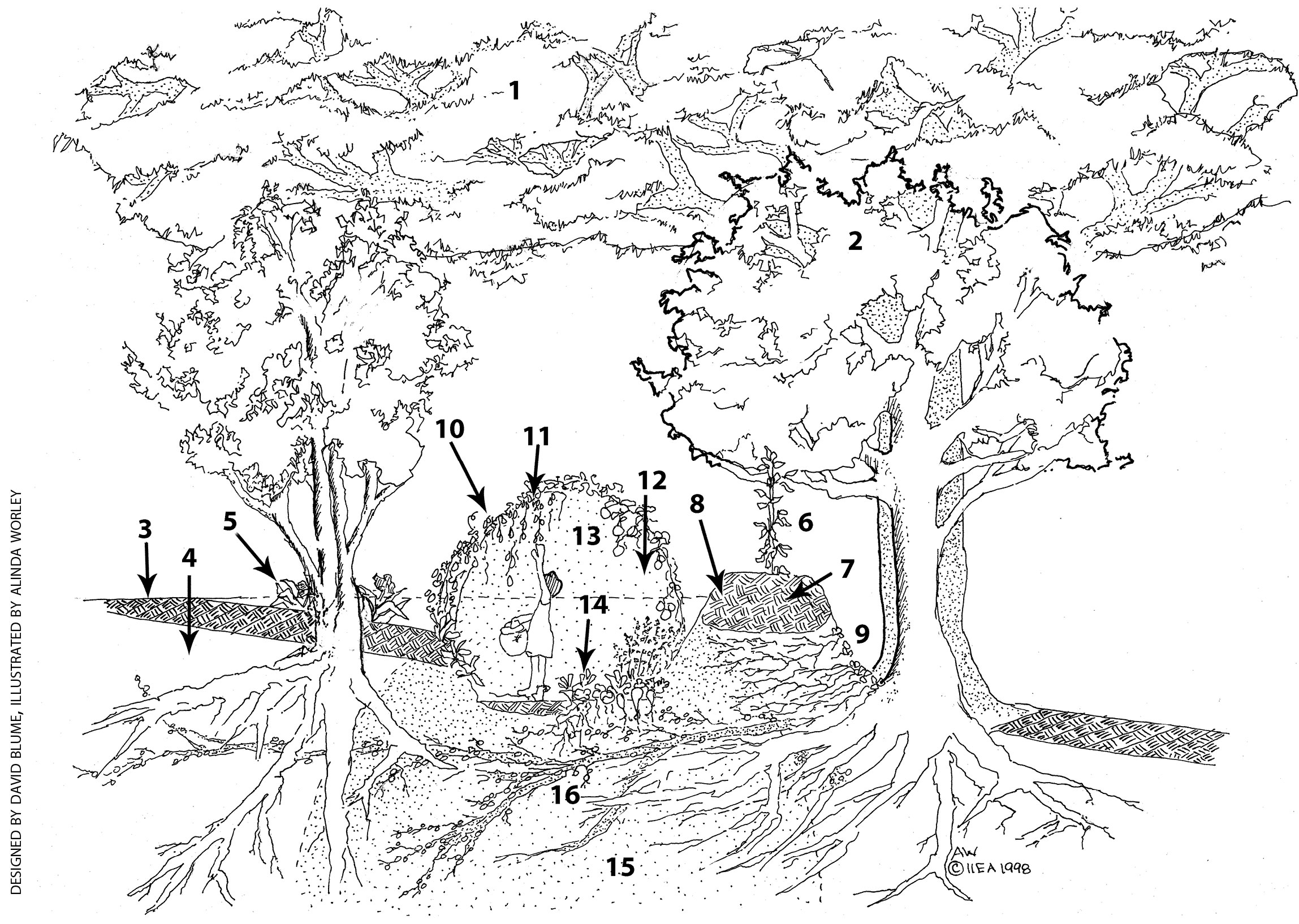

Fig. 3-5 Permaculture production system. In order to make the most out of scarce rainfall, this permaculture design uses a swale (a dead-level ditch, the interior area between the grade behind and the berm in front) to collect water as its primary feature. Although this particular design is focused on food and flower production, it could easily be altered slightly to focus on energy crops. Bear in mind this is a fairly simple design; it could be much more dense, yielding even more crops and profit. Starting from the top is (1) a wide-canopied, nitrogen-fixing, Farmer’s tree that provides light shade and bee forage. Understory trees (2) provide food or energy crops. Topsoil (3) is shown cross-hatched; subsoil (4) is shown white. Bulbs (5) are planted around bases of trees, generating a high-value flower crop while protecting trunk and roots from burrowing animals. Flowers or surface-harvested crops like nopales can be planted from the trunk out to the drip line. Drip line crops (6) such as trellised berries exploit the surplus moisture of this zone and are often planted on the well-drained part (7) of the swale berm (8). Berm faces can be planted in deep-rooted permanent crops such as strawberries (9), which root to six feet. Although shown here on only one face, such crops can be grown on all three faces of the swale (on the uphill side of the swale and the inside and outside faces of the berm). Over the swale, a trellis (10) increases cropping area. Beans or berries (11) or squash/cucumbers/melons/tomatoes (12) make good use of the trellis and provide shade (13). The shaded bottom of the swale has rich soil for high-value vegetable crops or even energy crops such as fodder beets (14). The swale bottom, with its air stabilized by the trellis crops, would also benefit from heavier-than-air carbon dioxide enrichment and irrigation with stillage. The shaded subsoil (15) is permanently hydrated by the water soaking in from rain. By the time the system has been operating for three years, there’s enough water stored there to irrigate the trees lining the swale for 100 years, even if it never rains again. Nitrogen-fixing bacteria (16) on the roots of the Farmer’s tree provide all the nitrate fertilizer needed by all the crops grown under its canopy. Mycorrhizal fungi in the top few feet of soil knit all the plants together, sharing the nutrients extracted from the soil and the carbohydrates provided by the upper canopies. One acre of integrated production like this would financially outperform 2000 acres of corn.

So, unlike what we learned in school, each plant and tree is not a self-serving species. They are all a community connected via fungi, which collect and distribute the surplus resources cooperatively. By growing under the light shade, a crop not only avoids photosaturation and thus can photosynthesize all day, it can also receive surplus sugar from the top canopy via the fungi, if needed.

This whole cooperative system is based on a keystone: There must be sufficient organic matter in or on the soil. As I said, soil below 2% organic matter causes this system to collapse. Using soluble chemical fertilizers will kill most of the soil microlife. Insecticides and herbicides are toxic to almost all microlife, as well, although many bacteria and some fungi have been able to break them down. (Good thing, too, or life on Earth as we know it would have ended!) Which brings us back to the significance of organic polycultural farming.

Dealing with Weeds and Pests

A well-designed agricultural system based on alcohol fuel-making can eliminate the need for Roundup herbicide, genetically modified Roundup Ready corn seed, chemical fertilizers, and even most insecticides. These are all losing propositions, anyway.

Insecticides rarely work very well. Biology responds to stimulus; biology “learns” and responds differently over time. Now, this doesn’t apply only to individual organisms; it even more appropriately applies to populations. Let’s say it’s the late 1940s and you have a surplus of grasshoppers that are eating your wheat. The agricultural extension agent brings you this new nerve gas called DDT, and you spray it over your crop. Wow, 98% of your grasshoppers stop hopping. It’s a miracle! You have more crop to harvest, and the stuff hardly costs anything. (Although you don’t seem to hear any birds or toads anymore.)

“If we throw Mother Nature out the window, she comes back in the door with a pitchfork.” —MASANOBU FUKUOKA, AUTHOR OF THE ONE-STRAW REVOLUTION: AN INTRODUCTION TO NATURAL FARMING

Next year, the hundreds of eggs laid by the surviving insects the previous year hatch, not having been gobbled up by predators, who were killed along with the insects last year. So the grasshoppers come back even worse, since there are fewer predators to eat them. No matter, you just spray your DDT. But this year is not like last year. You need to use twice as much DDT, since maybe 20% (not 2%) survive your first spraying this year. Why? Because you killed all the hoppers that were easily killed by DDT last year, and only the ones with natural immunity have survived to reproduce. Without predators, which reproduce more slowly, you have selected the hardiest of the bunch to come back this second year. So it takes a lot more pesticide to kill these resistant bugs.

The third year comes around, and there aren’t any birds, toads, fish, spiders, or snakes anymore—because the pesticide was in all the bugs they ate, and concentrated in their flesh, and killed them. So now you have to increase the use of DDT again, and this time you can kill only 20% of the hoppers. At this point, you generally lose the crop unless you drench it in DDT. By the fourth or fifth year, all the grasshoppers that have survived reproduce super-hoppers that not only are immune to DDT, but also excrete it through glands that produce the “tobacco juice” that has been sprayed on nearly every kid who has captured a hopper. The hoppers learn to squirt the juice into the mouths of predator birds, killing them with the pesticide.

To continue using pesticides, you need to escalate every two or three years to ever more toxic ones. As mentioned in Chapter 2, some of the pesticides used today are 3000 times more toxic than the original DDT.

So, since Nature responds to stimulus, its response to the toxins will vary constantly. Nature will overcome any obstacle we put in her path due to the incredible diversity of genetics each species has.

In polyculture farming, a mosaic and rotation of primary crops both confuses pests and limits the amount of food they will find suitable. Monoculture is like an all-you-can-eat buffet for the pests that like that particular crop. So pests that like to eat corn and overwinter in the soil will be mighty disappointed when they awaken to find the field planted to sugar beets in the spring. Root crop pests that love beets will find little tasty fare in the tough fibrous roots of sorghum. You can grow strips of flowering plants, such as Jerusalem artichokes, to provide high-protein food to keep insect predators fed while they wait for more bugs to show up; it will also provide you with an energy crop at the end of the farming season.

Rather than being drained for corn, natural low swampy areas could sport energy crops, such as cattails, that make ideal habitat for birds or beneficial insects such as dragonflies and for countless toads—all of which would go out and decimate the pests in adjoining fields.

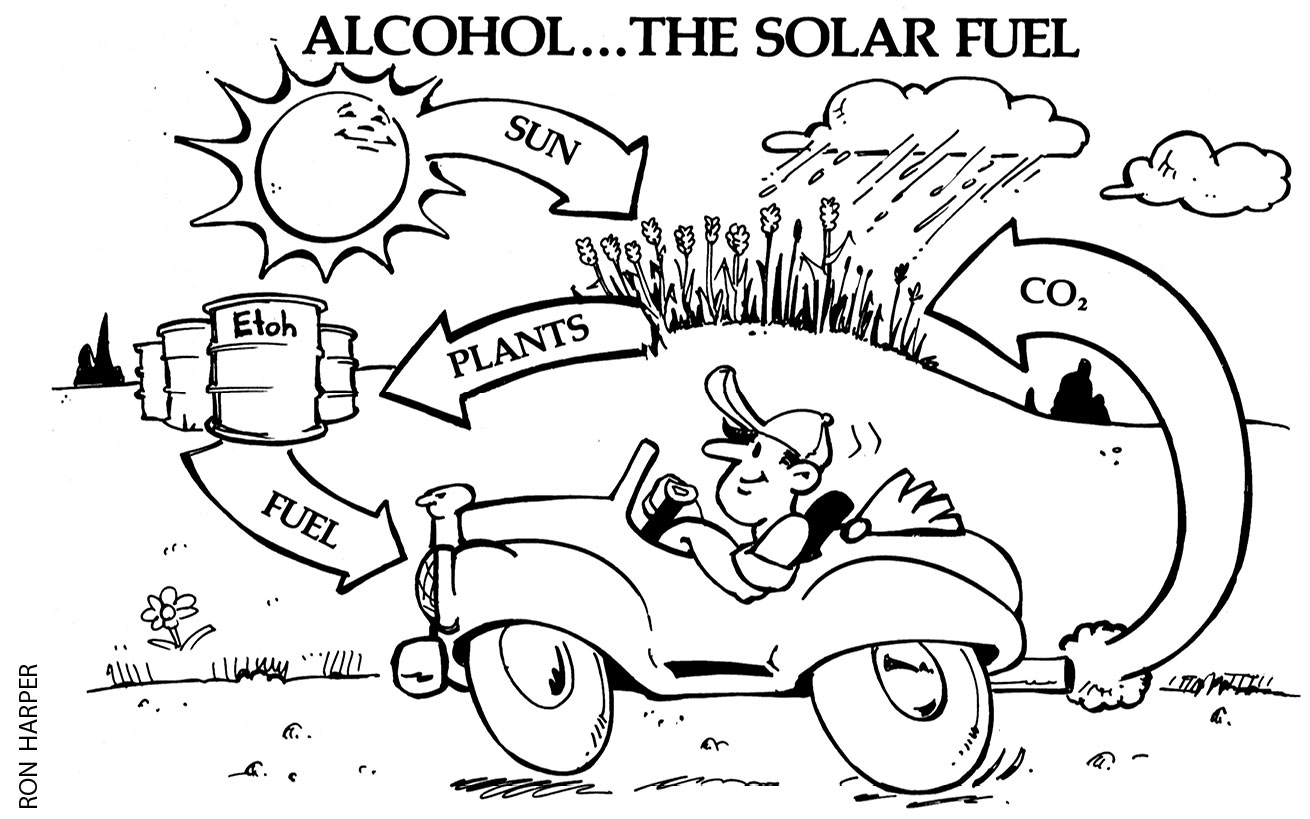

Fig. 3-7 Alcohol, the solar fuel. Alcohol is really liquefied solar energy. Using sun, carbon dioxide, and water, plants make the carbohydrates that we turn into alcohol. When burned, the solar energy drives our engines, while returning the CO2 and water back to be used by next year’s crops.

“All the world is waiting for a substitute for gasoline. When that is gone, there will be no more gasoline, and long before that time, the price of gasoline will have risen to a point where it will be too expensive to burn as a motor fuel. The day is not far distant when, for every one of those barrels of gasoline, a barrel of alcohol must be substituted.”

—HENRY FORD, DETROIT NEWS, DECEMBER 13, 1916

Organic “Weed and Feed”— Putting an End to Monsanto in Agriculture

Monsanto is the industry leader in genetically modified seed and is the supplier of Roundup. It is in the vanguard of companies that wish to shackle farmers to patented herbicide-resistant seed—which allows farmers to use lots of Roundup herbicide to kill the weeds growing between the GMO crop. Monsanto prohibits farmers from saving the seed and forces them to buy new seed each year. I have a remedy for this strong-arm tactic.

In permaculture, we always think back to what happens in Nature for an explanation. So, let’s observe corn in Nature to figure out how best to grow it without chemicals. When a cornstalk falls over at the end of its life, the husk-wrapped starchy ears of corn plop onto the ground. Over the winter, a little decomposition happens to the husk. Birds might get to the kernels on the top half of the cob, pecking some open, scattering bits of corn, but leaving some of the grain on the cob, where rain washes it onto the ground. Come spring, three, four, maybe a dozen intact seeds sprout and come rocketing out of the ground. Very few or no weeds seem to be near the corn when it sprouts. So, in Nature, the corn seems to have an herbicidal effect that gives the clump of corn a big head start. To this day, indigenous people plant corn in clumps imitating Nature.

An experiment I performed shows how easy it is to take herbicides out of the picture. For a long time, organic farmers had known that corn gluten meal (CGM) was a very good pre-emergent herbicide. This means that it kills plants when they are just sprouting, as opposed to post-emergent herbicides, which kill plants beyond the seedling stage. (The high price of CGM has limited its use to organic gardeners; it is too expensive for most organic farming.) No one knew how CGM worked, however. USDA scientists said that the prevailing theory was that weeds were nitrogen-poisoned by the high-protein gluten. It seemed a ridiculous theory, as most weeds I know suck up nitrogen better than most crops.

Based on my observation of corn in Nature, I conducted an experiment to see if the distiller’s dried grains with solubles (DDGS), the byproduct of dry-milling corn, would have an herbicidal quality similar to CGM’s. Remember, everything that came from the soil is in the DDGS. The only thing taken out of a crop to make alcohol is the solar energy. The plant carbohydrates contain only carbon dioxide, water, and sunlight. Nothing from the soil is used up in burning alcohol in cars. All the protein, fat, and soil minerals are still in the spent byproduct of the alcohol process.

I set up four flats with potting mix, and I put ten rows of weed seeds in each one. The seeds were for the ten worst weeds reported in cornfields. I reasoned that if anything would be resistant to the herbicidal effect of corn, it would be weeds growing in cornfields. I added nothing to the control flat, sprinkled whole organic corn meal (OCM) over the second flat, sprinkled CGM over the third, and sprinkled DDGS over the fourth. (I included OCM in the experiment to make sure that any herbicidal effect was not from the residue of chemical herbicides; organic corn is never treated with chemicals. Later testing of the DDGS showed that it, too, contained zero residual biocides.)

Fig. 3-8 Control group, plantings without DDGS. These rows are planted with the ten worst weeds found in cornfields. They are used for testing any new herbicide. In this flat, there was just plain fertilized soil, and in just a few days the weeds have come up rather nicely.

Plantings with DDGS. This photo was taken on the same day as the control photo. You can see most of the weeds did not survive germination, and the rest are severely stunted. Within days, all the weeds were finished off. You can just see the remains of the bacterial gel that formed on the surface of the soil as a result of the DDGS addition.

So did DDGS act like an herbicide? Yes, it did. In fact, all three materials had significant herbicidal effects, but the DDGS results were the most pronounced. About half the weeds were killed, and the rest were stunted. Stunting was enough, though, since the corn grew right up and buried the puny weeds in darkness, where they withered.

I did another trial at the same time to see if herbicidal qualities would inhibit the germination of corn. I seeded four flats with corn instead of weeds, and then treated them with nothing, OCM, CGM, and DDGS. The various additives delayed germination one day.

The granules of OCM, CGM, or DDGS were attacked by bacterial and fibrous fungal mycelia right away, which grew into the grains from the soil. The bacteria frequently formed water-holding gels, which adhered to both the grains and the soil particles. The filamentous fungi knitted the grains to soil particles in mats of webbing. This prevented soil erosion and seed washout by falling drops of water. It also created a breathable “seal” on the surface of the soil, limiting evaporation.

Next, there was an explosion of soil microlife eating the pioneering fungi, bacterial gels, and the DDGS. Within weeks, the mycelia, the bacterial gels, and the granules of DDGS disappeared. The fermented, ground seed in the form of DDGS had allowed things that like to eat germinating or broken seed coats to go through a powerful population explosion in the soil. These microbes really savaged the roots of sprouting weed seeds. Once this fungus and microbe explosion happens, it takes many weeks before any other seed trying to germinate in the bed has a chance to grow. Corn, however, was immune to the effect. The herbicidal control effect was biological, not chemical.

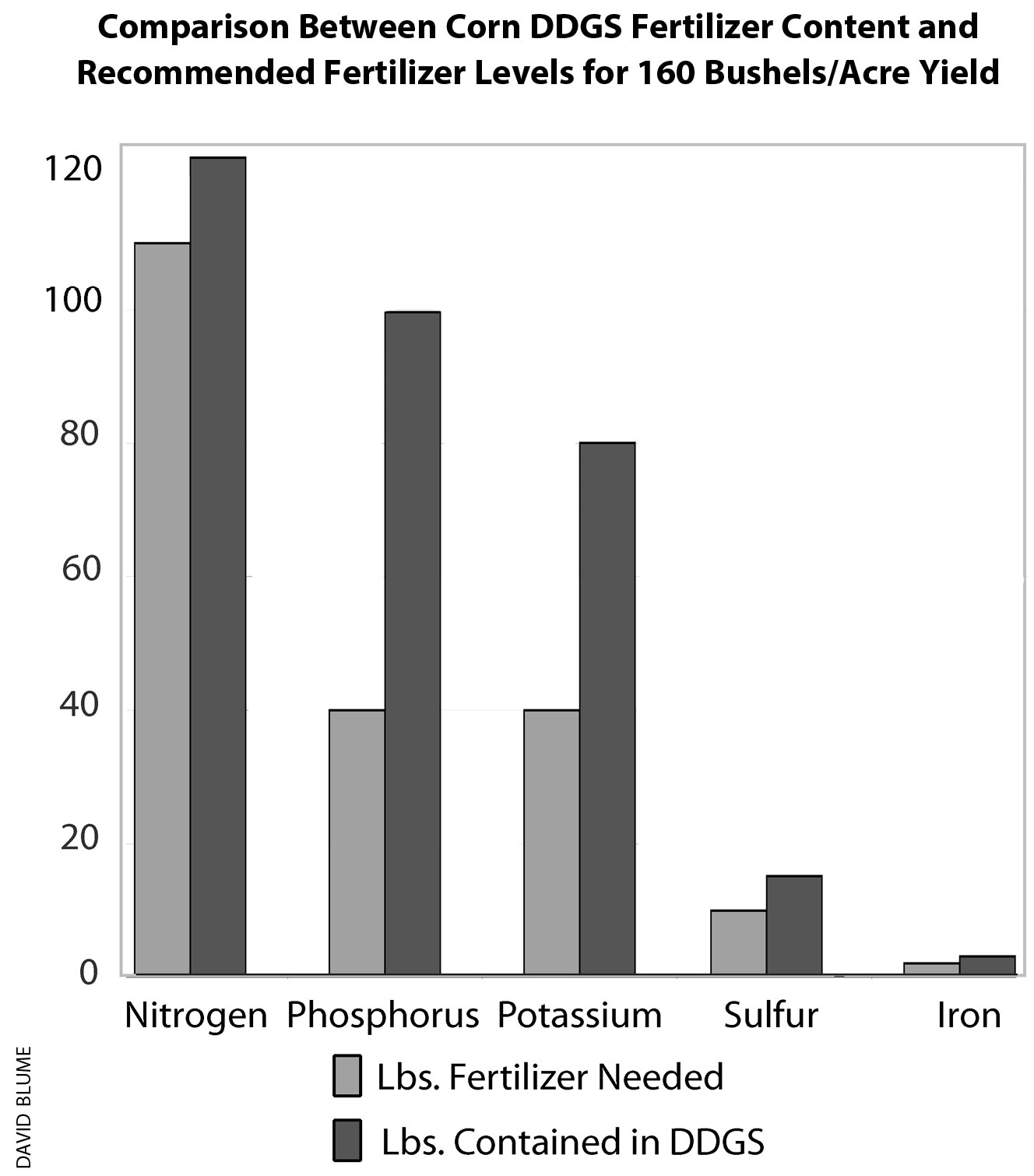

Fig. 3-10 Corn DDGS fertilizer value. You’ll note that the DDGS supplies considerably more nutrients than are needed to grow the next crop of corn, especially when it comes to phosphorus and potassium.

So how does this translate into a revolution in farming and an end to Monsanto’s formula of selling patented seed and herbicides to match, and still dramatically cut production costs?

According to USDA records, the median corn yield in the very average state of Nebraska was almost 160 bushels per acre.13 I had the DDGS in my experiment analyzed for its composition of soil nutrients, and then calculated how much DDGS would come from 160 bushels, and what would be the soil nutrient value of that amount of DDGS. It was then a simple matter of comparing these figures to what the USDA says it takes to grow the 160 bushels of corn in that average field.

I found that there was enough fertilizer value in the DDGS “left over” from growing 160 bushels of corn to raise more than the next 160 bushels, since there was actually 10% more nitrogen and an even greater surplus of other critical nutrients, such as phosphorus, potassium, iron, and sulfur, than was required to grow the next corn crop. Everything that came out of the soil to make that corn was still there in the DDGS. So, from the soil’s point of view, it was like returning last year’s crop nutrients for use by this year’s crop.

I found that this ratio of increased percentages of certain nutrients with repeated DDGS applications to corn held true even at yields of more than 200 bushels per acre. So, over a period of years, 160-bushel land would be producing 200 bushels. Plus, the soil organic matter would rise year after year after year. Combined with the soil-protecting effects of DDGS, the higher organic matter would mean more retained nutrients, increasing humus levels.

It would also mean relative drought-proofing of the crop, due to the mycelial sealing-in of moisture in the early phases of crop growth, and the sponge-like water-retention effect of organic matter.

What I had literally discovered in the experiment with DDGS was organic, drought-proofing, “weed and feed.”

Now, how would this affect a farmer’s bottom line and even free him from corporate dependence? Using very general numbers, you’ll find that a corn farmer historically grosses something like $250 per acre on his crop. For that acre, he spends more than $50 on toxic Roundup herbicide and Roundup Ready genetically modified herbicide-resistant seed. He spends about $80–$100 in fertilizer per acre and a smaller amount on insecticides. With all his expenses totaled, a farmer will generally net, in a decent year, about $50 on an acre of corn.

But if the farmer produces alcohol instead of selling his grain into agribusiness—and takes the DDGS that results from his grain-growing, and applies it to his field during soil prep and planting—his costs to produce that acre of corn will drop from $150 to about $50, tripling the net profit.

And remember, the farmer is now making alcohol from his grain, instead of selling it cheap for animal feed. If the farmer sells his alcohol to a community-supported energy alcohol distribution station, he can bring in, after deducting the cost of making the alcohol, $1.50 per gallon, or $588 per acre, instead of getting $250 selling corn for animal feed.

The net profit from his crop would be over $500 instead of $50. He wouldn’t have to borrow money for fertilizer or GMO seed (since he could now save his own), and he would have, of course, no herbicide costs. This could be big news in Farm Country. Instead of corn being a soil-draining crop in rotation, it could be soil-building. Never again would a single year’s crop failure bankrupt a farm.

Fig. 3-11 Improved growth of corn using DDGS. On the left is corn in fertilized potting soil, and on the right is corn in the same soil with DDGS added to the surface. Neither patch is nutrient-deficient, but clearly the addition of the DDGS has improved the growth of the crop on the right. In the original color photo, the difference is even more marked.

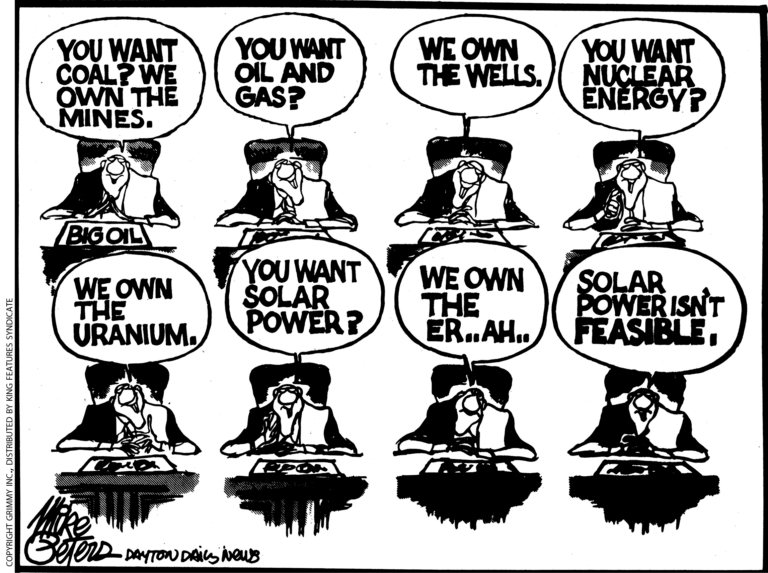

Once a farmer starts to farm with DDGS, even if he only does it every other year or one in every three years while rotating through other energy crops, he is within an inch of being organic—which is better for the environment, his family’s health, and his bottom line. The Oilygarchy—which sells more than one billion pounds of insecticides per year, as much as four billion pounds of herbicides per year, and an ungodly amount of highly energy-intensive nitrogen fertilizer, made from natural gas—would be deprived of a high-value market for its products. Monsanto would have no one to sell its proprietary GMO seed or chemicals to. Now, this would really be a farmers’ revolution.

So here is my contribution to the revolution. I was granted a patent in 2007 on the process to use DDGS as a combination fertilizer and herbicide. Now an agribusiness corporation cannot patent it and then prevent others from using it. I am going to handle use of my patent in a completely different manner than a large agribusiness corporation would. A program will be set up to let individual farmers and small collectives with small capacity license this patent for a nominal fee, perhaps only requiring registration (details are still being worked out as of the publication date of this book).

I ask the following three things of these small-volume users of my patent: 1) that they not use chemical herbicides and not use genetically modified seeds; 2) that they learn how to breed and save their seed from season to season; over time, you will end up with a variety tailored to your climate and soil (write me if you need help with this); and 3) in lieu of the patent royalty, donate what you think is fair to the International Institute for Ecological Agriculture so that I can keep doing this kind of work. Make sure that you take care of your family and workers first. I trust my fellow small farmers to do right by me if their profit increases. So take that, Monsanto!

Alcohol fuel production can result in more concentrated corporate farming of monocrops processed in giant plants, or it can save the family farm and provide farmers with markets for a wide variety of crops. The preferable route to a sustainable agriculture system looks to me like farmers cooperatively producing fuel and multiple co-products in small plants, using a wide range of feedstocks, from roots to grains to cellulose.

That sort of mosaic would go a long way toward eliminating the pest and soil problems that monoculture has created, as well as eliminating the use of toxic chemicals and fertilizers in an attempt to mitigate those problems. Such diversity would make for a more resilient farm economy with less chance of failure than the high-risk gambling involved in growing only corn and soybeans. Ideally, a sustainable agricultural system would be three-dimensional, harvesting three times as much sunlight as biomass. It would have mixed canopies of trees, and ground crops whose environmental needs closely match the local climate and solar income.

As you will see in Book 2, Chapter 11, farms can become producers of many value-added human foods and products, rather than just the suppliers of low-cost raw materials to corporations. Alcohol fuel production sets us on the road to a permanently productive and fossil-fuel-free agriculture.

Endnotes

3-1. Stephen R. Gliessman, “Multiple Cropping Systems: A Basis for Developing an Alternative Agriculture,” in Charles A. Francis, Multiple Cropping Systems (New York: Macmillan, 1986), 72–76.

3-2. Mark Avery, email communication, Agência Estado website, reprinted in Grain Journal and Biofuels Journal, www.grainnet.com (March 9, 2005).

3-3. Brazilian Department of Sugar and Ethanol, Sugar and Ethanol in Brazil, Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Food Supply Secretariat of Production and Commercialization, January 2005, 4.0.

3-4. Brazilian Department of Sugar and Ethanol, 8.

3-5. Brazil: Future Agricultural Expansion Potential Underrated, USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, January 21, 2003, www.fas.USDA.gov/pecad2/highlights/2003/01/Ag_expansion/ (September 21, 2003).

3-6. “Where the Oil Is,” compiled from statistics in Oil & Gas Journal.

3-7. “Who Consumes It,” compiled from U.S. Energy Information Administration tables on world petroleum consumption.

3-8. David Tilman, Jason Hill, and Clarence Lehman, “Carbon-Negative Biofuels from Low-Input High-Diversity Grassland Biomass,” Science 314:5805 (December 8, 2006), 1598–1600.

3-9. S.B. Idso and B.A. Kimball, Responses of Sour Orange Trees to Long-Term Atmospheric C02 Enrichment (USDA ARS), 2.

3-10. Idso and Kimball.

3-11. John N. Klironomos and Miranda M. Hart, “Food-Web Dynamics: Animal Nitrogen Swap for Plant Carbon,” Nature 410 (April 5, 2001), 651–652.

3-12. Elaine Ingham, Ph.D., communication with author, 2005.

3-13. Nebraska Agricultural Statistics Service, Nebraska Agri-Facts 17/2002, www.nass.USDA.gov/ne/agrifact/agf0218.txt (September 4, 2002).

© 2008–2026 David Blume.

More About Organic Alcohol

Profitable Surplus: Sargassum Solutions

eBook Available for Alcohol Can Be a Gas! Fueling an Ethanol Revolution for the 21st Century

David Blume’s Appearances on Coast to Coast A.M. Radio Show

13 Reasons to Use Alcohol Fuel

Organic Alcohol

R. Buckminster Fuller’s Foreword to Alcohol Can Be a Gas!

Just How Inefficient Is Oil Production Anyway?

The Process and Benefits of Double Fermentation

Sustainable Agriculture’s Role in Climate Change

A Clear, Attainable Path to Thriving Without Fossil Fuels

David Blume’s Clean Homegrown Energy

About Carbon Dioxide in the Air

Meat-Eating Trees

David Blume’s Classic Talk on Alcohol Fuel

David Blume: Flex-Fuel Cars and Alcohol Cookstoves

How George Washington Encouraged Moonshining